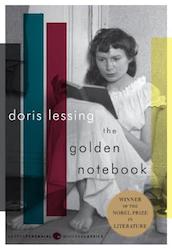

Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook is another of the works featured in Pop Chart Labs’ scratch-off poster, 100 Essential Novels. Published in 1962, it’s considered by most critics to be Lessing’s most important novel. Lessing was prolific, writing some thirty novels before her death in 2013. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2007.

The Golden Notebook is heralded by critics as a precursor to both postmodernist fiction and feminist fiction (although Lessing didn’t consider it a feminist book).

Anna Wulf, the narrator, is a novelist suffering from writer’s block after a successful debut work. She’s trying to work through the block by writing in four different journals, compartmentalizing her life and work. The black notebook, “which is to do with Anna Wulf the writer; a red notebook, concerned with politics; a yellow notebook, in which [she] makes stories out of [her] experience; and a blue notebook which tries to be a diary.”

The novel is broken up into six sections, with a storyline from Anna, followed by entries in the four notebooks. Toward the end of the novel, she puts the four notebooks away in an attempt to reintegrate the parts of her life as she begins writing solely in a fifth, the golden notebook.

The novel is experimental in form and language, leading into the postmodern notion that language doesn’t describe reality, but in fact, determines it. But that also means this novel is difficult to read. There are many characters, some fictionalized versions of Anna’s own life, and she makes it even more complicated by reusing names from her life in her fictions. It’s a challenge because chronology is rearranged and the vast cast runs into each other.

The two main women in the novel, Anna and her actor friend Molly, are what Lessing is calling “Free Women,” women who choose to live outside of the conventions of the 1950s. Neither is still married, and for many years, they enter into a series of affairs, but every single one of their partners is a married man, and an asshole. I can see where the growing feminist literature latches on to this work. My big problem with seeing this as a major feminist work is that the characters aren’t people. They’re easy stereotypes, and easy targets. All of the characters are awful people, and I find it impossible to care about any of them.

My big problem with this novel isn’t the endless analysis of communism, or the problems of the women in a male-dominated society. I understand that as the basis of what she’s developing. What bothers me is the fact that Anna (on the point of madness at times) cannot live life; she can only think about it, in agonizingly unnecessary repetition. She never gets out of her head and it’s mind-numbingly tedious. Five or six times, I felt I’d sprain an eyebrow when she launched into yet another pages-long discourse on nothing, (e.g., a four-page essay on the philosophical implications of grasshoppers mating).

I have no doubt intellectuals love this novel because it’s complicated, high-brow, and pretentious. It’s why I dislike so much postmodern fiction. The authors (and critics) are in love with playing games and philosophical flights of fancy. It’s ultimately very elitist and for someone who reads a novel first and foremost for an actual story, it makes for a maddening experience. If this hadn’t been on one of my “must reads” lists, I would have DNFed it after the first 50-75 pages. I probably should have, because after 635 pages of smallish print, nothing changed.

The Golden Notebook is heralded by critics as a precursor to both postmodernist fiction and feminist fiction (although Lessing didn’t consider it a feminist book).

Anna Wulf, the narrator, is a novelist suffering from writer’s block after a successful debut work. She’s trying to work through the block by writing in four different journals, compartmentalizing her life and work. The black notebook, “which is to do with Anna Wulf the writer; a red notebook, concerned with politics; a yellow notebook, in which [she] makes stories out of [her] experience; and a blue notebook which tries to be a diary.”

The novel is broken up into six sections, with a storyline from Anna, followed by entries in the four notebooks. Toward the end of the novel, she puts the four notebooks away in an attempt to reintegrate the parts of her life as she begins writing solely in a fifth, the golden notebook.

The novel is experimental in form and language, leading into the postmodern notion that language doesn’t describe reality, but in fact, determines it. But that also means this novel is difficult to read. There are many characters, some fictionalized versions of Anna’s own life, and she makes it even more complicated by reusing names from her life in her fictions. It’s a challenge because chronology is rearranged and the vast cast runs into each other.

The two main women in the novel, Anna and her actor friend Molly, are what Lessing is calling “Free Women,” women who choose to live outside of the conventions of the 1950s. Neither is still married, and for many years, they enter into a series of affairs, but every single one of their partners is a married man, and an asshole. I can see where the growing feminist literature latches on to this work. My big problem with seeing this as a major feminist work is that the characters aren’t people. They’re easy stereotypes, and easy targets. All of the characters are awful people, and I find it impossible to care about any of them.

My big problem with this novel isn’t the endless analysis of communism, or the problems of the women in a male-dominated society. I understand that as the basis of what she’s developing. What bothers me is the fact that Anna (on the point of madness at times) cannot live life; she can only think about it, in agonizingly unnecessary repetition. She never gets out of her head and it’s mind-numbingly tedious. Five or six times, I felt I’d sprain an eyebrow when she launched into yet another pages-long discourse on nothing, (e.g., a four-page essay on the philosophical implications of grasshoppers mating).

I have no doubt intellectuals love this novel because it’s complicated, high-brow, and pretentious. It’s why I dislike so much postmodern fiction. The authors (and critics) are in love with playing games and philosophical flights of fancy. It’s ultimately very elitist and for someone who reads a novel first and foremost for an actual story, it makes for a maddening experience. If this hadn’t been on one of my “must reads” lists, I would have DNFed it after the first 50-75 pages. I probably should have, because after 635 pages of smallish print, nothing changed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed