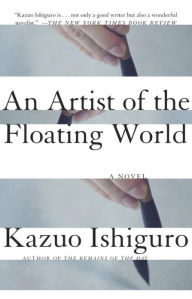

An Artist of the Floating World is the second of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels–part of my run through his entire oeuvre this year. And like A Pale View of Hills, it has a very quiet, subdued feel to it.

Masuji Ono is the narrator, a painter of some reputation. The story takes place in 1949-1950, but much of it is the narrator remembering his early career before World War II.

Over time, we start to learn that something in Ono’s wartime past is hanging over him. As he considers the marriage negotiations for his younger daughter, we start getting more and more hints that something in his past might hurt the negotiation process, but he’s very hesitant to discuss what it is.

Like so many first-person narratives, it’s hard to discern how reliable Ono is as a narrator for much of the novel. He speaks modestly about his own accomplishments and the adoration of his students, but at times it’s a false modesty as he is clearly proud of the reputation he held in the art world. He also speaks quite often about the limitations of his memory as he worries whether he is recalling dialogue accurately.

In the end we do learn what his guilt stems from, but as an outsider who doesn’t understand in any meaningful way Japan’s post-war guilt and sense of defeat, I can’t really appreciate what he did as all that important, yet it clearly is within that society. So for me, the second half of the novel didn’t live up to the first half, but I suspect that’s my own failing and not Ishiguro’s.

I thoroughly enjoy his writing style, however, and as I said, the first half of the novel flew by for me. I look forward to getting to read the rest of his novels soon.

Masuji Ono is the narrator, a painter of some reputation. The story takes place in 1949-1950, but much of it is the narrator remembering his early career before World War II.

Over time, we start to learn that something in Ono’s wartime past is hanging over him. As he considers the marriage negotiations for his younger daughter, we start getting more and more hints that something in his past might hurt the negotiation process, but he’s very hesitant to discuss what it is.

Like so many first-person narratives, it’s hard to discern how reliable Ono is as a narrator for much of the novel. He speaks modestly about his own accomplishments and the adoration of his students, but at times it’s a false modesty as he is clearly proud of the reputation he held in the art world. He also speaks quite often about the limitations of his memory as he worries whether he is recalling dialogue accurately.

In the end we do learn what his guilt stems from, but as an outsider who doesn’t understand in any meaningful way Japan’s post-war guilt and sense of defeat, I can’t really appreciate what he did as all that important, yet it clearly is within that society. So for me, the second half of the novel didn’t live up to the first half, but I suspect that’s my own failing and not Ishiguro’s.

I thoroughly enjoy his writing style, however, and as I said, the first half of the novel flew by for me. I look forward to getting to read the rest of his novels soon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed