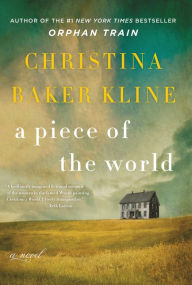

Ever since Tracy Chevalier’s Girl With a Pearl Earring (1999), I’ve been a big fan of fictionalized histories of art works, whether paintings or music. So when Christina Baker Kline’s treatment of a famous Andrew Wyeth painting (Christina’s World) came out, it was an easy choice for me. And I had already thoroughly enjoyed her previous novel, Orphan Train.

The novel is told in fragmented chronology throughout the 20th Century, but chronicles most of the life of Christina Olson, the inspiration and model for the figure in the foreground of Wyeth’s painting. Christina is an extremely bright young girl, but suffers from an unidentified neural disorder that leaves her legs and arms only partially functional. As a result, she leaves school at a young age and her world shrinks to the limits of her family farm in Maine. And as she gets older, she loses all use of her legs, literally having to drag herself from one spot to the next.

The narrative feels very quiet and constrained to me, perhaps mirroring Christina’s reserve and interior life. Much of the book is about the interplay of fate, free will, and chance. Do we really make choices in our lives, or are they made for us and we have only the illusion of choice? And there are no pat answers in the novel, just the act of questioning.

While the novel is Christina’s story, it’s also the story of generations, lost family members, lost love, and the odd friendship that grows up between Christina, her brother Alvaro, and the young Andrew Wyeth, as he strives to make his way in the art world and out of the shadow of his famous father, N.C. Wyeth.

In the end, Christina longs for just one thing in life, to be seen and understood, not just pitied. And this painting, perhaps, is the evidence that at last, someone has really seen her.

The novel is told in fragmented chronology throughout the 20th Century, but chronicles most of the life of Christina Olson, the inspiration and model for the figure in the foreground of Wyeth’s painting. Christina is an extremely bright young girl, but suffers from an unidentified neural disorder that leaves her legs and arms only partially functional. As a result, she leaves school at a young age and her world shrinks to the limits of her family farm in Maine. And as she gets older, she loses all use of her legs, literally having to drag herself from one spot to the next.

The narrative feels very quiet and constrained to me, perhaps mirroring Christina’s reserve and interior life. Much of the book is about the interplay of fate, free will, and chance. Do we really make choices in our lives, or are they made for us and we have only the illusion of choice? And there are no pat answers in the novel, just the act of questioning.

While the novel is Christina’s story, it’s also the story of generations, lost family members, lost love, and the odd friendship that grows up between Christina, her brother Alvaro, and the young Andrew Wyeth, as he strives to make his way in the art world and out of the shadow of his famous father, N.C. Wyeth.

In the end, Christina longs for just one thing in life, to be seen and understood, not just pitied. And this painting, perhaps, is the evidence that at last, someone has really seen her.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed